Part 2 – Continuation from David Dobbs column

How culture, passion and genetics are fueling a Nigerian takeover of U.S. sports

There are other cultures that stress education and family. Why are Nigerians different to be the subject of this talent/recruiting boom?

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was a direct result of the growing civil rights movement. It relaxed immigration quotas. The Refugee Act of 1980 made it easier for African immigrants to travel to the US. That was important for those fleeing conflict-impacted areas, such as Nigeria.

That Nigerian U.S. population of 376,000 is roughly the size of New Orleans. That sample size has produced an athletic revolution.

WNBA players Chiney and Nneke Ogwumike — from the Houston suburb of Tomball — were the only other siblings besides the Mannings to be drafted No. 1 overall in a U.S. professional sports league (2012, ’14).

They are part of the fabric of a metro area. Half of all African immigrants in Houston are from Nigeria

“Why is there such a concentration in Houston?” asked Stephen Klineberg, a sociology professor at Rice. “It’s the classic story of immigration. You go where you know people. You go there because your cousin is there.”

And the climate is roughly the same. The humidity and warmth of Houston is similar to Lagos. That gives rise to some of the first families of Nigerian-American sports — the Achos, the Orakpos, the Okafors.

All-American linebacker Brian Orakpo came out of Houston to win a national championship at Texas. He has been selected for the Pro Bowl in half of his eight pro seasons.

Emeka Okafor was the first member of his Nigerian family born in the United States. The former UConn basketball star and No. 2 overall draft pick played 10 NBA seasons. Distant cousin Jahlil Okafor was the No. 3 pick overall in 2015 out of Duke.

The Nigerian surge in athletics is best described another way: Half of all Nigerians have arrived in the country since 2000. Twenty-nine percent of those immigrants age 25 or older hold a master’s degree. That’s compared to 11 percent of the overall U.S. population. Eight percent of those Nigerians hold doctorate degrees compared to 1 percent of the U.S. population. This 2008 story calls them the most educated ethnicity in the U.S.

The NCAA’s antiquated bylaws constantly remind us a degree doesn’t necessarily equal an education. But in the Nigerian culture, education is the foundation for life.

Sam Acho could have played anywhere. His athletic talent was evident. But he was also being recruited by elite schools including several in the Ivy League. Sonny had to be convinced Texas was worthy of his son.

“Sam got into Texas’ McCombs School of Business,” Sonny said. “That solved the problem. Mack Brown basically knew we were strong people. Anything outside of that was going to cause a problem. They allowed us to be involved in the boy’s lives. It’s all about academics first and football second.”

In 2010, Sam won the Campbell Trophy, the so-called “Academic Heisman” for the nation’s top football scholar-athlete. Sam has a master’s in international business. Emmanuel has a master’s in psychology.

As kids, they led somewhat of a cloistered life. Such is the influence of parents. Sonny said former USC coach Pete Carroll once pulled Sam from a group of 300 and tried to get him to commit.

So you can sort of understand a natural skepticism.

“My kids couldn’t do sleepovers,” Sonny said. “I don’t know what you have going on in your house. … I’m not willing to let my son go over there and something goes wrong and then they accuse my son of raping … many African parents will be like that.”

A large part of this story is simple math and demographics. Nearly 16 percent of the United States’ population has ties to Africa, and nearly five percent of its immigrant population is from Nigeria. The only countries in the world larger than Nigeria are Pakistan, Brazil, Indonesia, the United States, India and China. According to a new United Nations report, Nigeria will be the third-most populous country in the world by 2050, overtaking the United States.

There are more native Nigerians in the U.S. than from any other African nation. In 1980, that number was 25,000. As the refugee laws began to loosen, in every decade from the 1980s through the 2000s, at least 10 million immigrants came to the U.S.

Eighty-eight percent of those were of Asian, Latin American, Caribbean or African descent, Klineberg said.

“It’s a new immigration stream that has never existed before in American history,” he added.

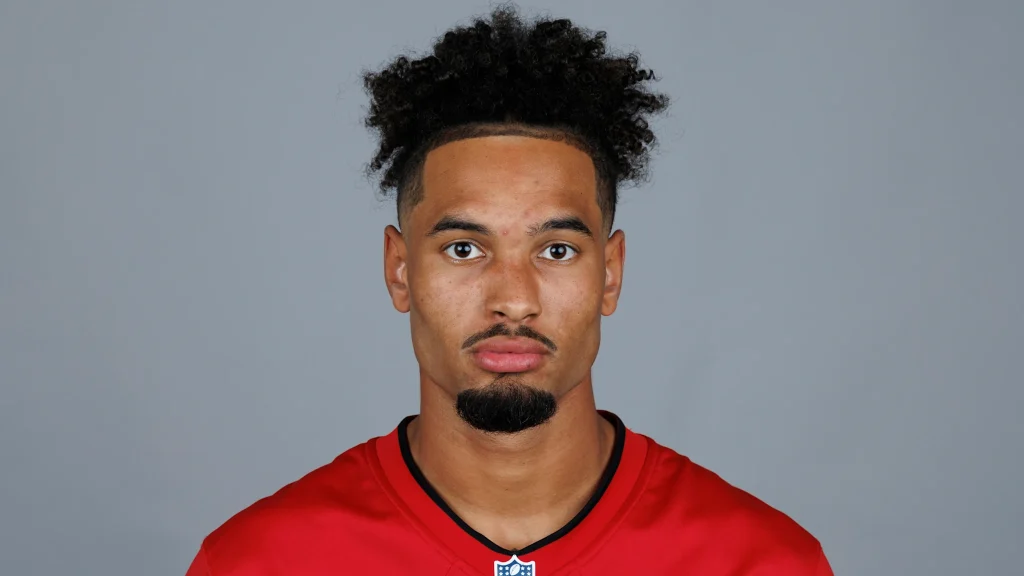

Nigerian families tend to be large, accomplished and — as mentioned — extremely close. Florida State All-ACC defensive tackle Derrick Nnadi says he talks to each of his six siblings daily via social media.

“Every day we have a whole group chat,” he said.

A brother, Bradley, is an actor in Southern California. A sister, Ashley, got into the nursing program at Old Dominion. Derrick somehow ended up the kid with his hand in the dirt — although one with a 3.12 grade-point average last semester.

“I have four jobs,” Derrick said. “Go to class, study, get conditioned, play football. That really boils down to two jobs.”

You shouldn’t even have to ask. Consider his father, Fred Nnadi. He came to the U.S. with his brother decades ago determined to carve out a life as an engineer.

But like a lot of immigrants, he was hindered by his nationality and the language barrier.

“I have so many brothers and sisters,” Fred said. “We were in the hundreds. He was a very great man. I have to tell you, when you look at Derrick, he’s black and big. … You’re looking at my father.”

That memory of Chief Ezeoha explains some of the why the 6-foot-1, 312-pound Derrick became one of three “Seminole Warriors” on the team by throwing up 525 pounds on the bench.

USC tight end Daniel Imatorbhebhe was born in Nigeria but grew up in suburban Atlanta before signing with Florida and immediately transferring to USC.

Imatorbhebhe’s mother is a biomedical consultant. His father worked for a mortgage company before the financial crash. His brother, Josh, is a Trojans receiver.

“It’s tough because it’s like we’re not really seen as in the some mold as an African-American kid,” Daniel said. “Teammates have always said, ‘Y’all are just built different. What do you attribute that to? Is it what you eat?'”

Yes, if you consider Nigerian staples oxtail, coconut rice and fufu the diet of champions. The family is also Yoruba, another common tribe in Nigeria.

“We’ll speak Pidjin [English] sometimes when we don’t want people to know what we’re saying,” Daniel said.

Six years ago, Moralake Akinosun was a promising teenage sprinter from Chicago. One day the Nigerian native randomly tweeted the hopes and dreams of a 16-year-old girl: Graduate from college, go to the Olympics and win a gold medal. She accomplished all three.

The gold medal sprinter at the 2016 Rio Olympics recalled her days on the Texas track team.

“It’s known that track and field is full of African-Americans,” Akinosun said. “There are more Nigerians than there are black people. There were 15 or 20 [Nigerian track athletes at Texas]. There were more of us.”

Her point: Not everyone in America makes the distinction between the two.

“Africans don’t consider themselves black, they consider themselves Africans,” said noted author Jon Entine, who is also executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project.

“American blacks can call themselves African-Americans, but they really are Americans. It’s a whole different mindset in cultural history and tradition and pride [from Nigerians].”

Despite being born in Nigeria, Akinosun chose to compete for the United States, where she has spent the majority of her life.

“I’ve always competed for the U.S.,” she said. “I am proud to be Nigerian. I’ve lived here for as long as I can remember. It’s easier for me since I’m here.

“[But] I absolutely love being Nigerian. It is a culture that is so deep-rooted. There is a sense of welcoming and belonging when you meet Nigerians.”

Entine has concluded those with a West African ancestry have — in general — less body fat, proportionally more lean muscle mass and a higher percentage of fast-twitch muscles.

If this begins to walk a thin line of racial stereotyping, consider the Twitter handle of Akinosun: @MsFastTwitch.

“We’re mostly fast-twitch [muscle] fibers,” she said. “There has to be something a lot of Nigerian athletes have in common. There is something beyond our extreme work ethic. There has to be some genetic factor.

Olajuwon was an impact 7-footer who thrived on that aforementioned diet.

“I think the genes and the God-given talent,” he said. “… The intelligence, the culture, the diversity; There are a lot of factors that play together.”

Ayeni, that man who knows the pipeline, agrees.

“First of all, the thing about Nigerians is they have distinguishing traits,” he said. “They have fast-twitch muscles. They’re very chiseled, very tough. It’s the same thing when you think of the Polynesian culture. You think of big, strong, thick torsos.”

Again, why? Other cultures stress education. Other cultures stress family. Other cultures are strong and driven.

“There are a billion people in India,” Tina Ayeni said. “When I watch the Olympics … I’ll have friends who are from India, I’ll joke, ‘Where is your team?’

“Routinely they’ll say sports is not something that is promoted in the culture. In Nigeria it is.”

Soccer is the country’s national sport. Olajuwon opened the door for basketball. In 2012, Nigeria was the only African nation to qualify for the Summer Olympics through the FIBA qualifying tournament.

Few know the Milwaukee Bucks‘ “Greek Freak” Giannis Antetokounmpo has Nigerian parents.

But ancestry is not necessarily destiny.

“What is it about people’s ancestry about how they succeed in sports?” Tina Ayeni asked. “Different populations have people who have potential. But that potential needs to be cultivated.”