Part One

Dennis Dodd a football columnist with CBS Sport, recently wrote a column on:

How culture, passion and genetics are fueling a Nigerian takeover of U.S. sports

Dennis Dodd the diehard St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Blues hockey fan, who graduated from the University of Missouri School of Journalism wrote about how Bobby Burton, the 47-year-old Houston native who had been covering college football recruiting for more than 20 years. With increased frequency, the best players he saw were more Americanized than American.

Burton a writer for 247Sports who lives in a Houston recruiting hotbed, had an increasingly recruiting quandary from what he had seen. Who were these kids with the strange names? They were polite, dedicated and often studs.

They absolutely were Nigerian, or the second-generation offspring of Nigerians, playing the hell out of American football.

All of it made sense when Burton did the math. Nigeria is the seventh most populous nation in the world (190 million). There are more Nigerian immigrants in the United States (376,000) than anywhere in the world. The Houston metro area is home to most Nigerians in the country (about 150,000).

Somehow their culture, their drive, their family structure and, oh yes, their bodies seemed to fit football.

With some meticulous research, Burton determined that in the 2016 NFL Draft there were as many players taken from Lagos, Nigeria, as from the city of Chicago (three).

“Unbelievable, unbelievable,” said Hakeem Olajuwon, the acknowledged pied piper for Nigerian athletes after coming out the University of Houston in 1984 and becoming a member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

According to Dodd, “I think it was kind of that moment in time,” Burton said. “It’s gone past the point of coincidence … It’s no longer just [an] anomaly. It’s part of the fabric of football and football recruiting in this country.”

Their story goes beyond college football — or even college athletics. Forget any athletic stereotype, Nigerians have a fierce family pride and dogged belief in education — particularly higher education — that allows them to succeed in this country.

These noble West African natives and their descendants are the American Dream.

“There is an honor about them,” USC coach Clay Helton said. Helton counts at least five first- or second-generation Nigerians on his roster.

“They’re such a regal people,” said Chris Plonsky, the women’s athletic director at Texas.

Oh, and they can play. In the space of four picks at the end of the first round and beginning of the second of that 2016 NFL Draft, three were of Nigerian descent

- (Ole Miss‘ Robert Nkemdiche,

- Texas A&M’s Germain Ifedi

- and Oklahoma State‘s Emmanuel Ogbah).

While the NCAA doesn’t keep statistics on nationality (only race), Nigerian influence on college sports is obvious. Among the Power Five, only the SEC didn’t have at least one player of Nigerian heritage on its all-conference first or second teams in 2016.

The past three seasons, at least one player of Nigerian heritage has finished in the top 25 nationally in tackles.

At least 80 players of Nigerian ancestry have populated professional football, soccer, basketball and even car racing in recent years. In 1987, Christian Okoye (“The Nigerian Nightmare”) became the first Nigerian-born NFL player.

Before Okoye, Olajuwon was the inspiration.

“You’re totally right,” said Emmanuel Acho, a Nigerian-American who played linebacker at Texas and in the NFL.

Hakeem’s background in soccer and handball helped his footwork in basketball.

But what about the scores of second-generation Nigerians — those born into a family with at least one Nigerian-born parent? In the 2016 NFL Draft alone, there were three times as many Nigerian players with hereditary ties to the country’s dominant tribe — the Igbo — (six) than draftees from Florida State (two).

Talking about the next rising stars

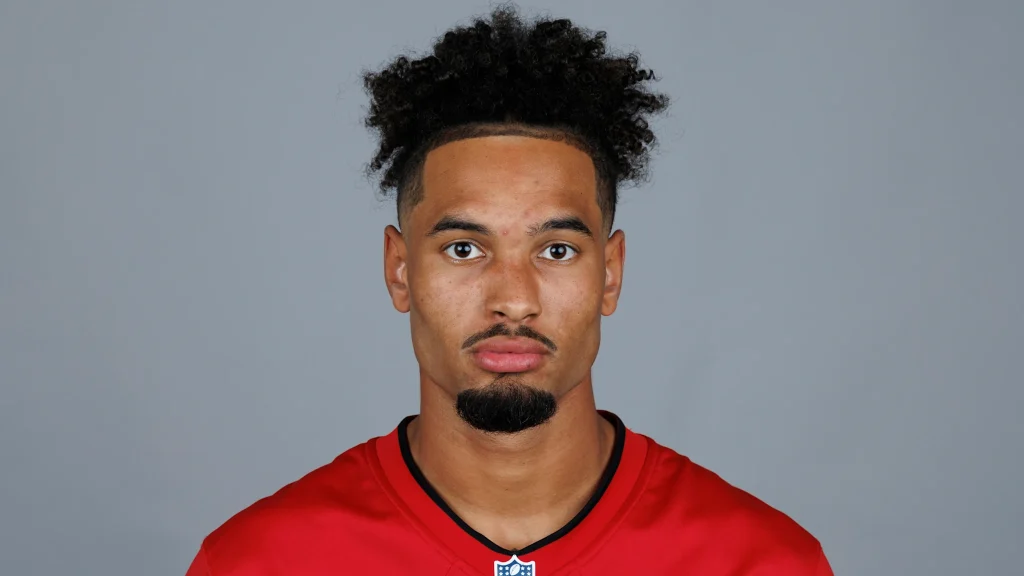

First is Oluwole Betiku might be the next Nigerian phenom in the NFL. The sophomore linebacker is already the talk of Southern California, where they affectionately call him “Wole” (woe-lay).

Betiku was discovered at a basketball camp in Nigeria. At age 15, he rode 11 hours in a bus to that camp in hopes of finding a better life for his impoverished family.

Sonny Acho, father of Sam and another Texas/NFL linebacker, Emmanuel – who has become an icon not only in his Dallas community but also for his Nigerian outreach quoted;

“We have oil everywhere,” as he speaks of his native land (Nigeria).

“We have a corrupt culture: Get all you can!” he said of Nigeria. “Only a few politicians live large. Millions live in poverty. These are the people that we are trying to go help.”

Sam and Emmanuel have been on an estimated 15-20 mission trips back to Nigeria. They have recruited friends and teammates to provide basic needs to villages.

“People talk about modern-day miracles,” Sam explained. “I saw a lady that was blind, and she received her sight through prayer.”

That required some reconfirmation. The mission trip did include some doctors who were removing cataracts.

“She starts praying, praying, praying,” Sam said. “The next thing she says is, ‘Amen.’ I’m standing around the way just kind of seeing what’s going on. The lady starts freaking out. They hold up this card and ask her what color it is.

A more conventional miracle: Out of that Nigerian camp, Betiku eventually got referred to former Penn State star LaVar Arrington, who became his legal guardian and brought him to the U.S. Betiku didn’t take up football until he was a sophomore at Serra High School in Los Angeles.

At that point, he was so naïve to the sport, Wole shed his shoulder pads as an annoyance. Just getting on the field for the Trojans for five games as a freshman was a win.

“I’ll never forget him absolutely breaking down into tears one day in our defensive team meeting,” Helton said. “They had showed some tape on him and a little bit of praise. He said, ‘Coach, if you could imagine where I was a couple of years ago to where I’m sitting right now. I just thank God for this opportunity.'”

Another top shot is Lou Ayeni. who is as plugged in to the Nigerian recruiting scene as anyone. Both parents of Iowa State‘s running backs coach are from Lagos, Nigeria’s capital.

Babs and Flora have PhDs. Dad is a statistical engineer. Mom is a biomedical statistician. One sister, Tina, is a nationally noted oncologist who treated the mother of Iowa State coach Matt Campbell.

“She’s trying to find a cure for ovarian cancer,” Lou said. “My mom makes fun of me. You went to Northwestern to coach football? I don’t understand it.”

That was after playing tailback and safety for the Wildcats under Randy Walker and surviving eight surgeries in his career. That was after his mother all but hand-picked the elite school for her son.

“My mom says, ‘You’re going to the best academic school you can go to,'” Lou recalled. “I was high school player of the year in Minnesota. I was enamored with Wisconsin. My first Big Ten visit was Iowa. They were really intriguing schools to me.”

Flora then interjected: Nothing is happening until you visit Northwestern.

Running back Kene Nwangwu was the state high jump champion out of Dallas, not the kind of player who come to Ames, Iowa. He was offered by every Big 12 school. Iowa State got him.

“It was an easy sell — 4.0 GPA, yes sir, no sir.”

Ayeni says he can see Nigerian talent just by watching tape.

“Some of them,” he said. “If I hear the name and watch them, I’ll know if they’re Nigerian.”

Their names are often lyrical, peaceful and meant to convey both their faith and future — Blessing, Sunday, Passionate, Peace, Promise, Princess.

Former Iowa State offensive lineman Oni Omoile was part of a royal bloodline in Nigeria. His nickname on the team quickly became “Prince.”

“We know each other by our last names,” Sonny Acho said. “You give me somebody’s last name, not only will I know that person is from Nigeria, I will even tell you where the person is from. It tells you the tribe and the language the person speaks.”

“Acho” means “I have found what I’m looking for,” according to Sonny.

Burton, according to Dobbs; knows Nigerians by another definition, which is through their grades.

“I’ve been doing this a long time,” Burton said. “I can’t remember a Nigerian kid ever having grade problems. It’s not the physical nature of their ability. It’s the maximization of what they have.”